Dad was well known for the lengths he’d go to for a painting. Aircraft carrier landings, trips aboard Great Lakes freighters, drives in the middle of the night to a shipyard to scrounge for discarded props (my brothers and I thought he was out of his mind, but who can argue with the grin he wore driving all the way there?); dozens and dozens of interviews with survivors of shipwrecks, re-enacting a deck fighting scene (the USS Constitution in Boston, if memory serves), and on and on and on. There are dozens more, believe me. And though I could spend a few hours chatting with one of my siblings or mom to jog our memories, it’d be an exercise in what was, to us, hardly remarkable. Because he was always doing something like this. Always off on some adventure, excursion, expedition, or wild goose chase. And it wasn’t the frequency with which they happened that I recall the most. It was the normalcy.

Still, for all the regularity, the story I remember the best was a trip to the University of Michigan’s planetarium. I’ll have to ask my friend Pete the exact month and year (he never forgets these details from our high school days) because I don’t remember and because it blurs into all the other experiences. What I do remember, though, is the heat. The suffocating temperature inside the darkened building under the dome-shaped screen. It was onto that bowl of fabric the astronomer dad was collaborating with projected a calculated expanse of stars. And while the mercury rose every minute, dad sat on the ground holding up a canvas with one hand and with the other, painted each star. One by one.

Literally, one...by...one.

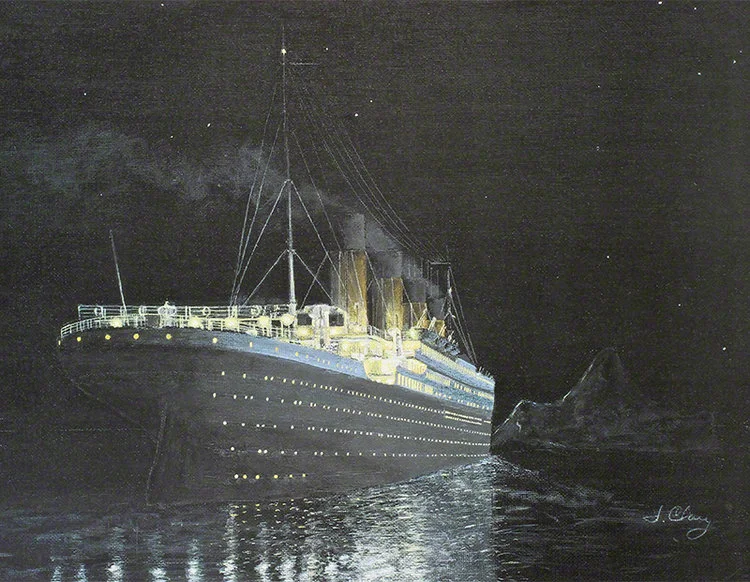

I’ll never forget the focused thrill on his face. I’ll never forget Pete and I ready to sell our souls to get out of what was, to us, abject boredom and stifling furnace. And I’ll never get over smiling now at what I didn’t care about then: that he was painting each and every visible star holding vigil in the sky the night the Titanic met her doom and sank to the bottom of the ocean where she would descend into legend and remain hidden forever. That is, until one day over seventy years later — precisely because of his rabid pursuit of details — he’d be among a crew of scientists and engineers searching for her final resting place.

Which, incidentally, they would finally discover because dad just so happened to remember a story everyone else dismissed as inconsequential.